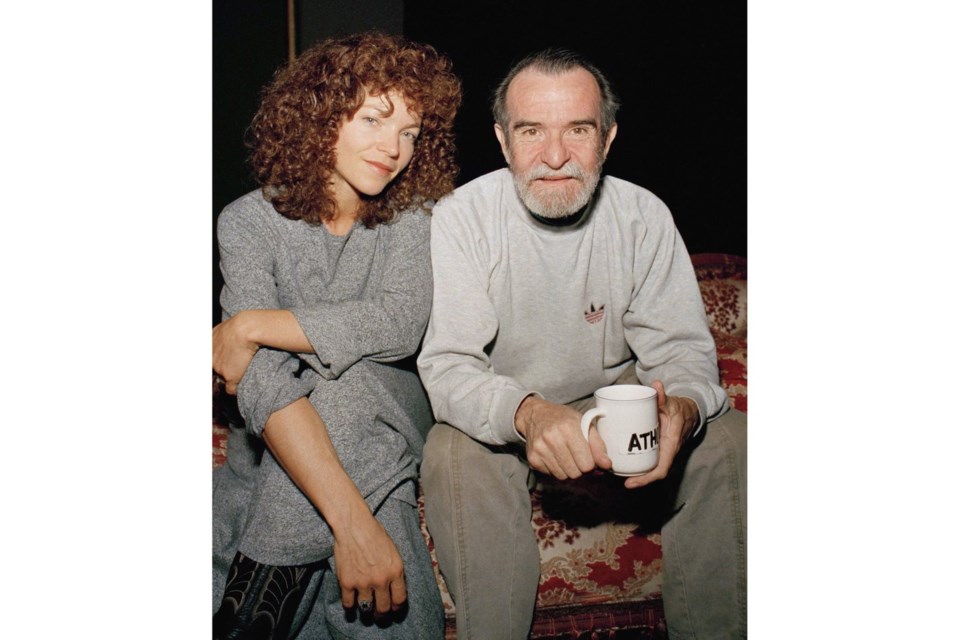

CAPE TOWN, South Africa (AP) ā Athol Fugard, South Africa's foremost dramatist who explored the pervasiveness of apartheid in such searing works as "The Blood Knot" and "āMaster Haroldā... and the Boys" to show how the racist system distorted the humanity of his country with what he called āa daily tally of injustice,ā has died. He was 92.

The South African government confirmed Fugard's death and said South Africa āhas lost one of its greatest literary and theatrical icons, whose work shaped the cultural and social landscape of our nation.ā

Six of Fugard's plays landed on Broadway, including āThe Blood Knotā and two productions of āāMaster Haroldā... and the Boys."

āThe Blood Knotā tells of how the relationship between two Black half-brothers deteriorates because one has lighter skin and can pass for white, which ultimately leads to him treating his darker half-brother as an inferior.

āWe were cursed with apartheid but blessed with great artists who shone a light on its impact and helped to guide us out of it. We owe a huge debt to this late, wonderful man,ā South African Sports, Arts and Culture Minister Gayton McKenzie said of Fugard.

Because Fugardās best-known plays center on the suffering caused by the apartheid policies of South Africa's white-minority government, some among Fugard's audience abroad were surprised to find he was white himself.

He challenged the apartheid government's segregation laws by collaborating with Black actors and writers, and āThe Blood Knotā ā where he played the light-skinned brother ā was believed to be the first major play in South Africa to feature a multiracial cast.

Fugard became a target for the government and his passport was taken away for four years after he directed a Black theater workshop, āThe Serpent Players.ā Five workshop members were imprisoned on Robben Island, where South Africa kept political prisoners during apartheid, including Nelson Mandela. Fugard and his family endured years of government surveillance; their mail was opened, their phones tapped, and their home subjected to midnight police searches.

Fugard told an interviewer that the best theater in Africa would come from South Africa because the ādaily tally of injustice and brutality has forced a maturity of thinking and feeling and an awareness of basic values I do not find equaled anywhere in Africa.ā

He viewed his work as an attempt to sabotage the violence of apartheid. āThe best sabotage is love,ā he said.

āāMaster Haroldā... and the Boysā is a Tony Award-nominated work set in a South African tea shop in 1950. It centers on the relationship between the son of the white owner and two Black servants who have served as his surrogate parents. One rainy afternoon, the bonds between them are stressed to breaking point when the teenage boy begins to abuse the servants.

āIn plain words, just get on with your job," the boy tells one servant. "My mother is right. Sheās always warning me about allowing you to get too familiar. Well, this time youāve gone too far. Itās going to stop right now. Youāre only a servant in here, and donāt forget it.ā

Anti-apartheid activist Desmond Tutu was in the audience when the play opened in 1983 ā at the height of apartheid.

"I thought it was something for which you don't applaud. The first response is weeping," Tutu, who died in 2021, said after the final curtain. āIt's saying something we know, that we've said so often about what this country does to human relations.ā

In a review of one play in 1980, TIME magazine said Fugardās work āindicts the impoverishment of spirit and the warping distortion of moral energy" that engulfed both Blacks and whites in apartheid South Africa.

Fugard was born in Middleburg in the semiarid Karoo on June 11, 1932. His father was an English-Irish man whose joy was playing jazz piano. His mother was Afrikaans, descended from South Africa's early Dutch-German settlers, and earned the family's income by running a store.

Fugard said his first trip into Johannesburg's Black enclave of Sophiatown ā since destroyed and replaced with a white residential area ā was "a definitive event of my life. I first went in there as the result of an accident. I suddenly encountered township life."

This ignited Fugard's longstanding urge to write. He left the University of Cape Town just before he would have graduated in philosophy because āI had a feeling that if I stayed I might be stuck into academia.ā

Fugard's theater experience was confined to acting in a school play until 1956, when he married actor Sheila Meiring and began concentrating on stage writing. He and Meiring later divorced. He married second wife Paula Fourie in 2016.

He took a job in 1958 as a clerk with a Johannesburg Native Commissioner's Court, where Black people who broke racial laws were sentenced, āone every two minutes.ā Fugard said he was broke and needed the job, but it included witnessing the caning of lawbreakers. āIt was the darkest period of my life,ā he said.

He got some satisfaction in putting a small wrench in the works, by "shuffling up the charge sheets," delaying proceedings enough for friends of the Black detainees to get them lawyers.

Later in life, Fugard taught acting, directing and playwriting at the University of California, San Diego. In 2006, the film āTsotsi,ā based on his 1961 novel, won international awards, including the Oscar for foreign language film. He won a Tony Award for lifetime achievement in 2011.

More recent plays include āThe Train Driver" (2010) and āThe Bird Watchersā (2011), which both premiered at the Fugard Theatre named after him in Cape Town. As an actor, he appeared in the films āThe Killing Fieldsā and āGandhi.ā In 2014, Fugard returned to the stage as an actor for the first time in 15 years in his own play, āShadow of the Hummingbird,ā at the Long Wharf in New Haven, Connecticut.

āā¶Ä

Kennedy reported from New York.

Mark Kennedy And Gerald Imray, The Associated Press