NEW YORK (AP) — “Take no prisoners — peacefully,” Carlos Santana sometimes tells his bandmates before taking the stage.

“I don’t like to coast. I don’t like to rope-a-dope,” Santana says. “I want to get in the middle of the ring and knock the sucker out. That way the referee can’t steal the fight from me.”

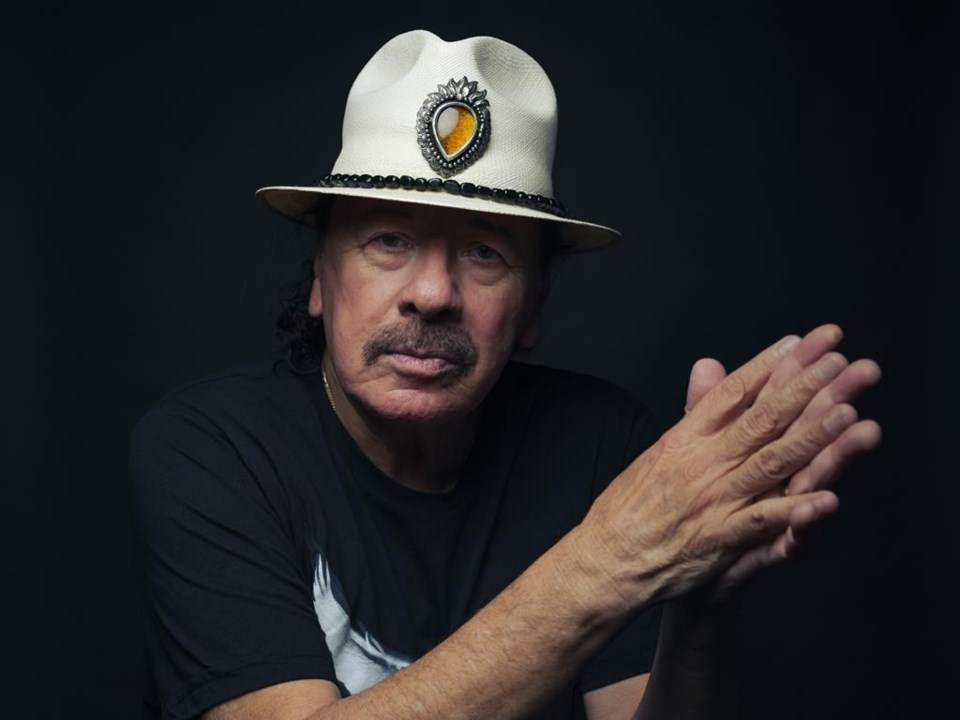

Santana, 75, can still whip a crowd into a frenzy like few others. He's been doing it since he stormed onto the San Francisco scene in the late '60s. He left the Woodstock audience dazed and stunned before the first Santana record came out.

The new documentary by Rudy Valdez, which is premiering at the Tribeca Film Festival and will be released this fall in theaters by Sony Pictures Classics, chronicles the meteoric rise of one of the most singular guitar players in rock history. The critic Robert Christgau once wrote: “He is less a man of style than of sound, a clear, loud, fluent sound that cleanses with the same motion no matter how often that motion is repeated."

Santana, who launches in Newark, New Jersey, on June 21, recently spoke by Zoom from his Bay Area home in California. He's been in San Francisco since his family (his father played the violin in a mariachi band) moved from Mexico in the 1960s.

“The Bay Area definitely attracts characters, you know?” said Santana. “Like Minnesota Fats or Les Paul. Rascals. I call them Divine Rascals.”

Santana, speaking with a panoramic photograph of the Woodstock performance hanging on the wall behind him, reflected on his journey, his sound and some of the demons he's faced along the way.

“I have nothing but good memories,” said Santana. “I have developed selective celestial amnesia.”

___

AP: How is it to watch a movie of your life?

SANTANA: It’s strange. It’s interesting to watch this person constantly strive and believe that he belongs. Ha ha! That he belongs on stage with these incredible musicians. Who would have thunk it that one minute I’m washing dishes at Tic Tock (Drive-In) and the next I’m on stage with Jerry Garcia and Eric Clapton and they’re looking at me like I definitely got something they want to learn from? They’d all go, “Where did you get that?” And I’d say, “Well, when you were listening to this, I was listening to a Hungarian gypsy musician named Gábor Szabó.” And also drummers. I learned a lot from African drummers. So I learned how to scramble the eggs differently. The guys from Creedence Clearwater used to say: “What is it you call that music you’re playing?” And I go, “African rhythms with blues guitar.”

AP: What was San Francisco like when you first arrived there in the '60s?

SANTANA: It was a it was a shock coming from Tijuana. In Tijuana, the people that I hung up hung around with were playing John Lee Hooker and Jimmy Reed and Lightnin Hopkins. We thought that B.B. King was sophisticated. Down and dirty, murky, simple but deadly, I think they call it cut and shoot crowd. Because if they didn’t like you, they'd cut and shoot you. They didn't want you to get all clever or sophisticated. They wanted you to just play the guts. So when I got here, it was a challenge. I basically thought that everybody knew John Lee Hooker. And then I got here and they were like, “Who?” I had to start all over again. Fortunately when I got here, the Rolling Stones were coming out and they were listening to the same things I was listening to. Little Walter and Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters. That's what saved me from getting frustrated and going back to Tijuana.

AP: Still, you were just 19 when you first performed at the Fillmore West.

SANTANA: Since I was a child, I got a reputation in Tijuana for playing the violin and winning most of the radio contests. When I came to the United States, I started winning a radio contest with a thousand bands. We were in the top three. Everything that I’ve done by grace, it gave me confidence that I can be on stage with Jerry Garcia or Michael Bloomfield or Peter Green, and later on Tito Puente and later on Miles Davis.

AP: Was there a spiritual element to music for you early on?

SANTANA: Everybody in this world needs a heartfelt hug to be reassured that we’re not going to be doomed hitting a brick wall, that we will go to the wall and we will succeed at becoming architects creating heaven on Earth. From Bob Marley to Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Same Cooke, they all talk about the same thing. “One Love.” “All You Need is Love.” “What a Wonderful World.” I make it a point to listen to certain songs that are like the new anthems of no church, but the new anthems of a galactic cathedral that transcends corrupt corporations and governments. If you and I get a chance to hitchhike a ride with Bezos or Elon Musk, and we take the space shuttle and go up there outside of the stratosphere and you look at the planet, there’s no flags up there. There’s no walls up there. There’s no time up there. When you say, “What time is it?” you just say, “It's now.” And so that’s how I try to play my music: Outside of time and outside of gravity. Maya Angelou said, “The only thing people are going to remember is how you make them feel.” And I was like, “Oh. So why don’t why don’t I make them feel their totality, their absoluteness?” I'm making somebody feel like they're from Kansas and they just put their toe in the Pacific Ocean in Hawaii for the first time. Bam! In one note.

AP: There are many enduring relationships you have in “Carlos” but how would you characterize your relationship to the guitar?

SANTANA: My guitar is my best lover, ever. Lovers come and go, but your relationship with the guitar — any brand or anything — stays. But it's your relationship with that sound. When you put your fingers on that note, you get chills. That's the best lover. You discover the sensation of getting the first French kiss. I'll stop there because this should be PG. But it all deals with the same thing. It all deals with “Oh my God.” The big G-spot, which is God. When you hit that, they all go, “Oh my God.” When you play music like that, it's more than just clever notes. It becomes emotion, feelings, passion. That's music to me. Music without emotion, passion or feelings is just clever noise. This is what's missing from the planet right now. People forgot how to feel. Stop, take a deep breathe and feel what your feeling.

AP: You have always had a distinct, instantly recognizable guitar sound, like a voice. Where did your tone come from?

SANTANA: I got it from my dad and I got it from my mom. I got it from my dad because he taught me how to play the violin and make one note with the bow, you know? And my mom, her tenacity and conviction. Her courage spilled on me. I used to lock myself in a closet in the dark and try to play like B.B. or Otis Rush, all the people that I love. And it used to frustrate me that I couldn't sound like that. Then one day I woke up and I go, “Hey, stupid. You’re not supposed to sound like them. They sound like them. You're supposed to sound like you.” Then you realized: “How do I play like me?" Just shut up and play. It's a real blessing and a gift that in one note you can be recognized out of thousands and thousands of guitar players around the world. It's like that with the people I love. John McLaughlin. T-Bone Walker. In one note, I can tell you who they are. There's a difference between Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell and Grant Green. But the one I listen to the most is still Otis Rush. There's something very raw and honest about the way he plays. Right now, I'm only listening to three things: Nina Simone, Etta James and Tina Turner. I want that sound that those women get in my guitar. I want my guitar to sound like a woman.

AP: In the film, you recount how Jerry Garcia gave you mescaline shortly before you took the stage at Woodstock, thinking you had hours before you performed. In arguably the most celebrated set of Woodstock, you were tripping and praying...

SANTANA: “God, please let me stay on tune and in time.” I could have laid a big egg in front of everybody. It was scary to look at the audience. But what came through was my mother's confidence: God is by your side. How can you go wrong?

AP: Were you accustomed to reaching different mental planes through the music, with or without drugs?

SANTANA: Outside of your mind is the best part is. There's not gravity there. There's no time. There's no criticizing. There's just pure manifestation. It goes from God through you to them. So I'm able to adapt myself, like with “Supernatural,” whether I'm playing with Lauren Hill, Rob Thomas or Eric Clapton. Whoever gets in front of me, you must listen and complement. I look forward to doing more things with Willie Nelson. I want to learn how to complement and simplify music with honesty.

AP: You said that your guitar neck then appeared like a snake to you. Did that ever happen to you again?

SANTANA: Eric Clapton and I talk about that because he used to do that as well. You could tell who visited that dimension. The Doors. The Beatles with “Sgt. Pepper's.” You could tell who went there because you can't play that music unless you go there. There's a part that's outside the realm of do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do. I guess you become like a mothership that can go anywhere in the universe and be relevant. Check out what I'm saying, man. To be 75 years old and to be relevant — because a lot of people invite me to play on their albums — is something to be grateful about. I feel that this is the best part of my life because it seems like now I know what I’m doing and why I’m doing it and for who I’m doing it. I am an architect of the highest order by Coltrane and Bob Marley. And with the gift of music, I'm able to create something that religion people cannot do and the United Nations cannot do and the United States government cannot do. Which is to bring to unity, harmony, oneness on Earth. Sound, resonance, vibration, frequency — those are my tools.

AP: In the film you talk about about being molested from the ages of 10 to 12. Did music bring some measure of healing from

SANTANA: All I can say with certainty and clarity is: I am not what happened to me. I still am, as God created me, with purity and innocence. I have a habit of sending people to the light instead of the hell. I used to say, “Eat s—- and die.” But I don't say that anymore. Now I go: You know what? I’m going to look at you like you’re 7 years old. And I'm going to send you into the light that is behind you. If I send you to hell, then I'm going to go there with you. And I don't want to go to hell. By doing that, I'm able to not be stuck with the victim mentality. “I'm Santana and I was a victim of child molestation" — I don't want to do that. I don't want to think like that. I'm Carlos Santana and by grace I can create blessings and miracles.

AP: Which, for many, you've done.

SANTANA: I like to offer people a way into your own divinity. That is the secret. The more we listen to “Sesame Street” or “Mister Rogers," the more we bring in that frequency that you are on divine. The opposite of that is that you're a wretched sinner. I tell people: Don’t sing that song when I die. Don’t sing “Amazing Grace.” Sing “La Cucaracha” or “La Bamba” or “Tequila” or “Who Let the Dogs Out.” Sing any f——ing thing but don't sing “Amazing Grace" at my funeral because there's nothing wretched about me.

___

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at:

Jake Coyle, The Associated Press